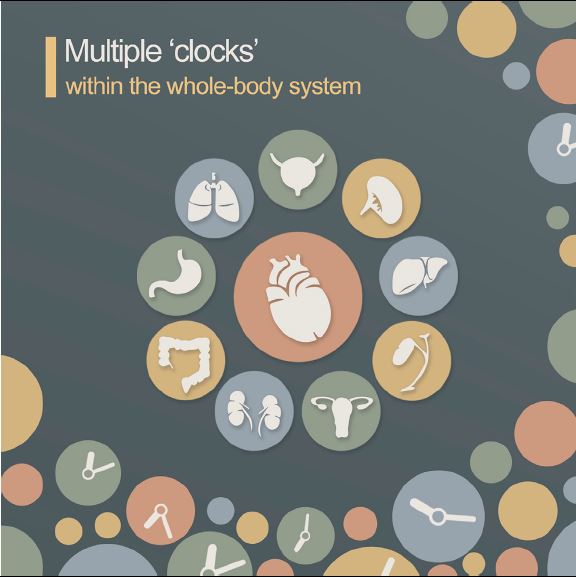

The picture illustrates the findings that organs and systems are aging at different rates. (Provided by the researchers)

BEIJING, March 9 (Xinhua) -- People are aging constantly, but individual organs have their own pace. The study published on Wednesday in the journal Cell Reports reported multiple "clocks" within the human body.

An international team led by Chinese scientists measured the varying biological ages of his or her organ systems.

They found that the biological ages of different organs and systems are not always in synchro, although healthy weight and physical fitness are expected to have a positive impact.

Having a more diverse gut microbiota indicates a younger gut, the study finds. However, it means a negative impact on the aging of the kidneys, which the investigators supposed that the diversity of species causes the kidneys to do more work.

Such inconsistency demonstrates the existence of multiple "clocks" throughout the whole body, according to the study.

They recruited 4,066 volunteers aged between 20 to 45 living in Shenzhen to supply blood and stool samples and facial skin images, along with examining physical fitness. Among them, 52 percent were female and 48 percent were male.

"We used biomarkers that could be identified from blood and stool samples plus some measurements from a routine body checkup," said the paper's co-corresponding author Xu Xun from the Beijing Genomics Institute and China National GeneBank in Shenzhen.

The investigators measured 403 features such as metabolism and immunity, and classified them into nine categories, namely heart, kidney, liver, sex, facial skin, nutrition, immunity, fitness, and gut microbiome.

Then they developed an aging-rate index to correlate different bodily systems with each other before judging volunteers either as aging faster or aging slower than their chronological age.

Some overweight individuals may have a faster aging rate related to their metabolism, while others may have a faster aging rate in their liver, according to the study.

Those findings could be used as intervention targets for improving health status as well as slowing down the aging process in the future, said the researchers.

Next, the researchers are planning to regularly follow up with the participants to validate their findings. Also the single-cell technology will be used to look at programmed aging in more detail.

The cell-to-cell variation in an aging individual will reveal important information about the heterogeneity within cell types and tissues, thus providing insights into aging mechanisms, said the paper's co-corresponding author Claudio Franceschi from Lobachevsky State University in Russia. ■