* Under Japanese rule, Okinawans face deep-rooted discrimination and injustice.

* Okinawa accounts for only 0.6 percent of Japan's territory but is home to about 70 percent of U.S. military bases in the country.

* 79 percent of respondents said they believe Okinawa Prefecture is overburdened by hosting U.S. military bases.

* U.S. military bases in Okinawa have largely constrained local economic development. The prefecture's per capita income is only about 70 percent of the Japanese average, the lowest level in the country.

by Xinhua writers Ye Shan, Hua Yi

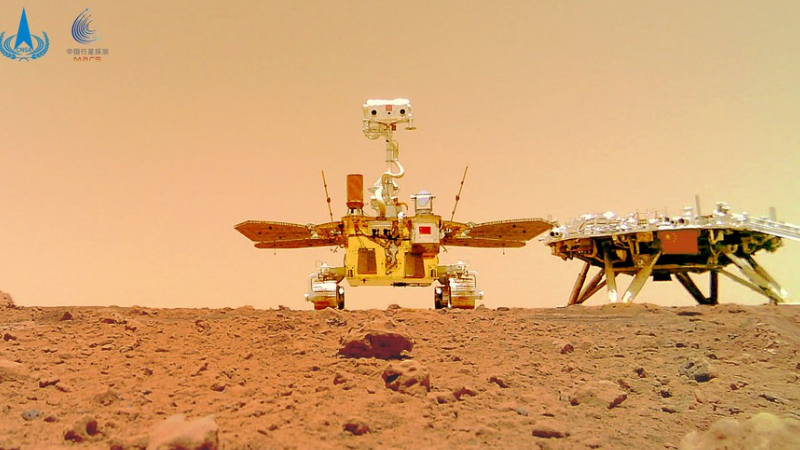

TOKYO, May 16 (Xinhua) -- The Japanese and the Okinawa prefectural governments jointly held an event in Tokyo on Sunday to mark the 50th anniversary of Okinawa's return to Japan in 1972 after 27 years of U.S. control.

Yet half a century after the official end of American rule, Okinawans remain overshadowed by a U.S. presence -- Okinawa Prefecture now hosts about 70 percent of U.S. military bases in Japan.

And while Okinawa now is a part of Japan, compared with their fellow citizens in other parts of the country, what the indigenous people of Okinawa have gained from the 50 years of Japanese governance is deep-rooted discrimination and a stunted economy.

A ceremony marking the 50th anniversary of Okinawa's reversion to Japan from the control of the United States is held in Okinawa, Japan, May 15, 2022. (Xinhua/Zhang Xiaoyu)

DISCRIMINATION FROM FELLOW JAPANESE

Historically, Okinawa was the independent kingdom of Ryukyu. After the Meiji Restoration, Japan annexed Ryukyu and established Okinawa Prefecture in 1879.

About a quarter of Okinawa's population died in the Battle of Okinawa in 1945, the worst of World War II in the Pacific battlefield. After the war, Okinawa was put under the "trusteeship" of the United States. In 1971, the United States and Japan secretly signed the Okinawa Reversion Agreement. The United States transferred the administration of Okinawa to Japan in May of the following year.

Under Japanese rule, Okinawans face deep-rooted discrimination and injustice.

Earlier this year, a high school student in Okinawa temporarily lost his vision after a police officer beat him with a baton. Hundreds of Okinawan youths barricaded a police station, throwing rocks and bottles in protest. Many Japanese netizens reviled them as "Dojin," a derogatory term for the Ryukyu people and other indigenous peoples, meaning "barbarians."

During a protest in Okinawa in October 2016, Osaka police officers clashed with Okinawans, with some officers calling protesters "Dojin." Japanese writer Shun Medoruma, who was at the protest site, said he had never felt more discriminated in his life upon hearing the remarks in person.

The then Governor of Okinawa Takeshi Onaga protested angrily, calling the term inappropriate.

However, Ichiro Matsui, the then governor of Osaka Prefecture, praised the police officers involved, saying that "the Osaka police are working hard to perform their duties, even if they didn't express themselves properly."

People take part in a protest in Okinawa, Japan, May 14, 2022, asking to reduce the U.S. base-hosting burdens of the southernmost prefecture of Okinawa. (Xinhua/Zhang Xiaoyu)

U.S. MILITARY BASES BECOME A NIGHTMARE

The Ryukyu Islands have long been regarded as an "outpost" and "fortress" in East Asia by both the Japanese and U.S. governments. Many U.S. military bases are maintained there.

Okinawa accounts for only 0.6 percent of Japan's territory but is home to about 70 percent of U.S. military bases in the country.

The U.S. military stationed in Japan is granted privileges like extraterritoriality, resulting in U.S. service members usually going unpunished even after committing a crime.

Safety accidents, aircraft noise and criminal incidents caused by the U.S. military have long been a bane of daily life for Okinawans.

According to statistics, from 1972 to 2019, U.S. troops and their families stationed in Japan committed about 6,000 crimes in Okinawa, including robbery, rape and murder.

In addition, traffic accidents by the U.S. military have caused more than 4,000 casualties. U.S. military aircraft have crashed and made emergency landings in Okinawa on several occasions.

What's more, Okinawa Prefecture has been the hardest-hit area in the sixth wave of COVID-19 in Japan since the end of last year because U.S. troops were not subject to quarantine restrictions when entering the country.

In the face of the various misdeeds of U.S. troops stationed in Okinawa, the Japanese government typically has no other choice but to verbally express regret, helplessly hoping that U.S. troops will "never do it again."

The Japanese public has had enough.

On March 14, thousands of people from across Japan took part in a mass rally organized by the Okinawa Peace Movement Center, an Okinawan civic group.

Etsuko Urashima, an activist in her 70s, said she considers Japan a U.S. dependency, hoping for a more autonomous Okinawa in the future.

People take part in a protest in Okinawa, Japan, May 15, 2022, the 50th anniversary of Okinawa's reversion to Japan from the control of the United States. (Xinhua/Zhang Xiaoyu)

BURDEN ON DEVELOPMENT

Despite the protests, U.S. military facilities in Okinawa have increased over the past 50 years, from 58.8 percent of Japan's total in the 1970s to about 70 percent today.

Okinawa Governor Denny Tamaki has recently submitted a "new proposal for a peaceful and prosperous Okinawa" to Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida. Calling the concentration of U.S. military bases in Okinawa a "structural and discriminatory problem," the proposal calls for alleviating the burden on Okinawa and realizing "an island of peace without military bases."

According to a public opinion poll released by Kyodo News on May 4, 79 percent of respondents said they believe Okinawa Prefecture is overburdened by hosting U.S. military bases.

According to the survey, 55 percent of respondents said they were "dissatisfied" with the development of Okinawa, and 83 percent said it is "unfair" or "generally unfair" for Okinawa to bear such a burden on its development compared with the rest of Japan.

U.S. military bases in Okinawa have largely constrained local economic development. The prefecture's per capita income is only about 70 percent of the Japanese average, the lowest level in the country.

Recently, a non-governmental organization consisting mainly of Okinawan aboriginal women issued a statement opposing the celebration of the 50th anniversary of Okinawa's so-called "return" to Japan.

"While the lives, pride and dignity of the Ryukyu and Okinawa people are still neglected and the military colonization continues, now is not the time for Okinawa to celebrate its 'return,'" it said. (Video reporters: Hua Yi and Zhang Xiaoyu; video editors: Jia Xiaotong and Yin Le)■