A drone photo taken on Dec. 3, 2025 shows a view of the cattle trading area of Huanggong Bazaar, Xinjiang's largest livestock market, in northwest China's Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. (Xinhua/Hu Huhu)

URUMQI, Jan. 18 (Xinhua) -- Huanggong Bazaar in Yining County of northwest China's Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region stirs even before dawn on trading days. Shrouded in winter darkness, trucks loaded with cattle, sheep and horses edge toward the gate at this bazaar, arriving in a sequence governed by the market rhythm that has changed little across generations.

Herders stream in both from nearby villages and distant pastures. Moving through the crowd with practiced intent is another group whose presence shapes the trade just as decisively.

Livestock brokers pace the pens, their attention trained on coats, teeth and joints. They read the animals closely, listen for the first signals of a deal, and position themselves between sellers who know their livestock and buyers who know their orders.

For generations, they were known locally as "cattle and sheep middlemen," a term tied more to crowded markets and hand-to-hand bargaining than to a recognized profession. In July 2025, that distinction shifted. China's human resources authorities formally designated "livestock broker" as one of 42 newly classified types of work.

For Ma Jun, a 47-year-old broker from the Hui ethnic group who works at the markets of Yining, this shift carries meaning beyond terminology. "Before, people called us cattle dealers," he said. "Now we're brokers. It sounds different. It feels different."

Xinjiang's largest livestock market, Huanggong Bazaar lies in the Ili River Valley, about 700 kilometers west of the capital Urumqi, at a historic crossroads along the ancient Silk Road. County records trace its origins to the mid-to-late Qing Dynasty (1644-1911). In 1907, Finnish explorer Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim photographed scenes at the bazaar in Ili during his travels through the region.

Today, the bazaar covers more than 40 hectares and can accommodate the simultaneous trading of roughly 25,000 head of livestock. More than a marketplace, it serves as a price barometer for live animal trade across Xinjiang.

Rising volumes have reshaped its rhythm. Since 2020, trading days have expanded from once a week to three days a week, falling on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays, as activity levels had outgrown the confines of a single market day. Weekly turnover now averages approximately 200 million yuan (around 28.5 million U.S. dollars).

On peak days, Wednesdays in particular, the bazaar draws 20,000 to 30,000 people. Livestock from across northern Xinjiang meets demand from buyers based as far away as south China's Guangdong Province, and Zhejiang Province and Shandong Province, both located in east China. Notably, market officials estimate that about one in five animals traded each week is transported out of the region.

In this crowded arena, brokers function as connective tissue between pasture and market. Many herders arrive with livestock but limited access to real-time price information. Buyers, often operating under tight delivery schedules, prioritize speed, scale and consistency. Brokers bridge the gap, helping herders sell and buyers secure animals more efficiently.

On busy trading mornings, Ma threads his way through densely packed cattle pens, often turning sideways to slip between animals. A short wooden stick in his hand taps a cow lightly, prompting it to shift so he can better judge its build. Red marking paint is kept in his pocket, ready to signal a deal. A wallet hangs across his chest, while his phone is always within reach.

"I walk tens of thousands of steps a day," he said. "That's how you find opportunities."

His movements appear casual, but his judgments are rapid and deliberate. He scans coat color, body shape and muscle distribution, checks joints by touch, and gauges temperament at a glance, focusing on animals with higher meat yield. When one meets his threshold, he calls out to the seller in Mandarin or the Uygur language.

Hands clasp. Prices are called aloud. Palms meet in quick, rhythmic slaps as the numbers rise and fall. Known locally as "hand-slapping bargaining," the exchange is a more transparent descendant of an older practice in which finger signals were hidden inside sleeves. A small ring of onlookers forms, offering encouragement via shouts or competing price estimates as negotiations inch forward.

When agreement is reached, Ma grips the seller's hand once more, marks the animal, and turns immediately to logistics. "Everyone has to be satisfied," he said. "The farmer, the buyer and us."

On very busy days, Ma brokers more than 100 head of cattle, with transactions approaching 1 million yuan in value.

Trust sustains this system. In a small notebook, Ma keeps the phone numbers of sellers whose animals he has placed. Payment often comes later. After the market closes and buyers' funds arrive, he transfers money to herders one by one. Thousands of brokers, herders and buyers operate this way, relying on reputations built over years.

Only those who understand the market and honor their word are able to endure. Ma recalled that early in his career, he sometimes misjudged animals. When cattle or sheep reached buyers and were deemed short on fat cover or meat yield, he compensated them out of his own pocket.

Experience sharpened his eye. Now, he said, a single glance is often enough. From coat, build and energy, he can usually estimate weight with confidence.

For Abduwayit Xaker, a Uygur broker from Altaoy Village in Yining County, the work begins even earlier. At 5 a.m. every Wednesday, he is already moving through rows of Ili horses, checking teeth and haggling over prices.

"Every horse has a temperament, just like people," he said. Such attentiveness has earned him the trust of clients from north China's Hebei Province, Shandong and Yunnan Province in southwest China. Last year, he brokered the sale of more than 3,000 Ili horses to buyers outside the region, generating an annual income of over 200,000 yuan.

In the market, locals call him the "far-seeing eyes for horses," as he is known for sensing what kind of horse will be needed far beyond the bazaar. The reward, he said, comes later, when buyers send videos of horses adapting to new environments, either on racetracks or in open grasslands.

The profession has evolved alongside technology. Where older middlemen relied on silent, sleeve-covered signals, Ma now sometimes turns to video calls, circling his phone around an animal to give distant buyers a live view. Some clients place orders without visiting the market at all, trusting his judgment.

Social media have become another tool. By posting short videos of Xinjiang livestock, Ma has reached new customers and expanded turnover, extending a market once bounded by geography into a network shaped by screens.

Infrastructure development has kept pace. Huanggong Bazaar now operates automated disinfection channels, quarantine facilities and on-site veterinary services. Financial service stations and an online trading platform support online transactions and capture data regarding volumes, categories and prices.

According to market officials, weekly transactions now exceed 20,000 head of livestock, with annual volumes surpassing 1 million animals.

For regulators, the formal recognition of livestock brokers reflects the important role they already played in rural economies. "It affirms their contribution, but it also raises expectations," said Wang Lei, an official with the bazaar's management office. Experience alone, he noted, may no longer suffice, as trade scales up and integrates more closely into national markets.

By midday, trading winds down. Trucks fill the bazaar again, this time heading out. Ma oversees the loading of cattle he has collected, some of which will wait in his own pens until enough volume is assembled for transportation.

In a place where commerce still unfolds hand to hand, his role -- now officially recognized -- has become indispensable. ■

Ma Jun selects cattle for a client at Huanggong Bazaar, Xinjiang's largest livestock market, in northwest China's Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, on Dec. 3, 2025. (Xinhua/Hu Huhu)

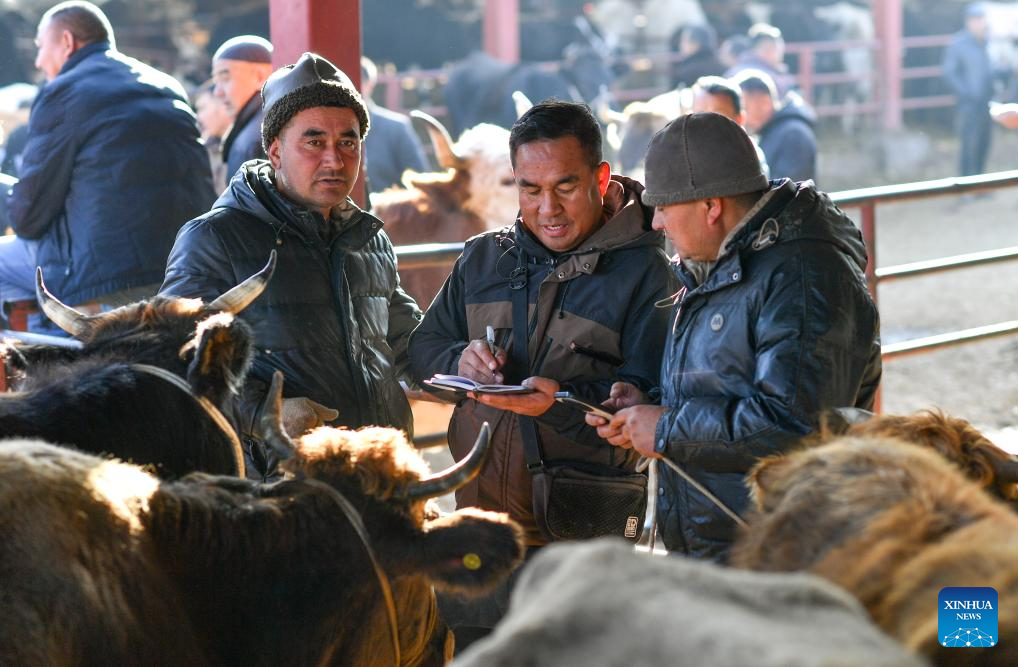

Ma Jun (C) records a seller's telephone number after purchasing his cattle at Huanggong Bazaar, Xinjiang's largest livestock market, in northwest China's Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, on Dec. 3, 2025. (Xinhua/Hu Huhu)

Ma Jun (R) shakes hands with a seller to seal a deal at Huanggong Bazaar, Xinjiang's largest livestock market, in northwest China's Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, on Dec. 1, 2025. (Xinhua/Hu Huhu)

An aerial drone photo taken on Dec. 3, 2025 shows a view of the horse trading area of Huanggong Bazaar, Xinjiang's largest livestock market, in northwest China's Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. (Xinhua/Hu Huhu)

An aerial drone photo taken on Dec. 1, 2025 shows a view of Huanggong Bazaar, Xinjiang's largest livestock market, in northwest China's Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. (Xinhua/Hu Huhu)