Mao Xianglin tells the road-building story at the village museum in Xiazhuang Village, Wushan County, southwest China's Chongqing Municipality on Jan. 16, 2024. (Xinhua/Tang Yi)

by Xinhua writers Yao Yulin, Chen Qingbing

CHONGQING, March 1 (Xinhua) -- A tough man like Mao Xianglin rarely hesitates in the face of difficulty, let alone being deterred from his course of action. However, faced with carving a road out of the mountains where he and his fellow villagers had lived for generations, he found himself faltering.

In the piercing winter of 1997, more than 100 villagers from over 300 households in Xiazhuang Village, southwest China's Chongqing Municipality, began the arduous task of building a road for vehicles on precipitous cliffs.

Lacking modern machinery, they hung themselves from the cliff-face and used hammers, drills and other simple tools to cut a slice in the stone. It was during this process that Huang Huiyuan, a local villager, was hit by a falling rock and fell into a gully 300 meters below.

Mao still remembers the scene as he and several other villagers descended by rope from the mountain top to the bottom of the gully. "We cried all the way. No one was not sad," he recalled.

The survivors were faced with the age-old question of "To be or not to be?" -- the universal quandary on whether to risk danger in pursuit of a better life or give up and accept one's fate.

Hidden in a steep-sided valley, fenced off by four cliffs, their hometown was secluded for hundreds of years. To reach the nearest town, the locals had to spend more than three hours clambering over hill and dale, following paths only suitable for foot traffic.

In 1997, Mao Xianglin, aged 38 at the time, mobilized his villagers to build a road suitable for vehicles, working at the task without external support. They all knew that, even if this road could be built, it was unlikely that their own generation would enjoy the benefits brought by convenient transportation.

At Huang's funeral, Mao, his heart filled with guilt and regret, asked villagers if they wanted to continue building the road.

Amid the silence, Huang's father was the first one to answer: "Let's build it. Let's keep this fire burning to the end. Don't stop now."

Through an agonizing reappraisal of life and death, they concluded that the road would someday bring the light of hope into the lives of their children or grandchildren, and for such a goal it was worthwhile risking their own lives.

In 2004, the 8-km road was finally finished, not only leading the locals to the outside world, but also leading the next generations to the greater dream -- common prosperity.

Today, self-motivated role models emerging from among the impoverished local residents of rural China, just like Mao, are called "pioneers of achieving prosperity." During China's battle against absolute poverty, such self-made pioneers are the key to setting a vivid example for other households living in grinding penury and driving distinctive local industrial development.

By 2025, China strives to cultivate 100,000 pioneers who will lead their fellow villagers to achieve prosperity through rural revitalization.

ROAD-BUILDING PIONEER

Before the road, death was a regular visitor to Xiazhuang.

When villagers wanted to reach the nearest town, they had to spend hours climbing the steep mountainside. If they needed firewood, they had to scramble over rocks to the mountain peak and cut down trees. In these indispensable routines, death and injury were inevitable.

Despite this heart-wrenching fact, when Mao proposed that the villagers should build themselves a road, many opposed the project, calling it a daydream.

In the 1970s, some senior villagers had tried to build a meandering byway, but this ended in failure. So they didn't hold out much hope for the vehicle-friendly road that Mao had in mind. Also, most villagers were poor and worried that such a road would cost money, and few were keen to face the safety risks of such a project.

However, Mao had traveled beyond the village and seen the changes taking place; he knew that a proper road was essential if the fate of the villagers was to be improved.

"When I was in the town, I saw that people were already using refrigerators and TVs, and driving cars. However, we were still chopping wood to cook and lived in adobe houses," he said.

Over the space of a month, Mao organized seven meetings and persuaded villagers of the necessity of building the road. "It's for ourselves, not for others," said Mao. "Don't be afraid of the sacrifice. Even if our generation doesn't enjoy the gains, the next generation will. No matter how many years it takes, we have to build this road."

Gradually, the villagers relented. Some of them, like Yang Yuanding, joined Mao in mobilizing others. Yang had seen his father hit by a falling rock when they were chopping wood, so he knew a road was needed to change the villagers' lives. Motivated by their hopes for the future, they decided to continue with the project.

Mao's success in leading the project is due in part to characteristics he shares with many other pioneers leading rural development, such as being raised in the village and being a member of the local community. In addition, many have usually acquired additional knowledge and experience from big cities through gig jobs, later returning to their hometowns to initiate pilot development programs, just like Mao.

Pioneers also need to be familiar with the local situation and to have built a certain amount of popularity and trust among the villagers, which provides a good foundation for their further explorations in pursuit of common prosperity. Since the pioneers are always local villagers, they have a certain amount of sway in the group and can organize them quickly to take part in the emerging business.

With the completion of the road in 2004, thanks to the vision of Mao and the villagers' hard work and courage, the story of Xiazhuang was rewritten.

THE RIGHT THING

Throughout the road-building process, Mao had demonstrated an unswerving determination and far-sighted vision. Many people were not just amazed at the "miracle" of the road itself, but also at how Mao came up with the idea, since he only received a middle school education and had stayed in the village most of his life.

"One must do boldly what is right," Mao said, adding that he still remembers that, although his family was very poor back then, his father, a retired soldier, always told him to do the right thing.

The so-called "right thing" sounded like a vague concept to Mao as a little boy, but he learned from other villagers and the well-worn phrases on their heads, which were almost the only sources of information he had access to during his childhood.

"Most families in Xiazhuang were poor, but we are very united. When every household experienced some difficulties, people would just offer to share food, firewood and so on," recalled Mao, who has himself been the beneficiary of such kindness.

When Mao was in his 30s, his father passed away, and warm-hearted villagers donated enough firewood to see his family through for a whole year.

The signature slogans often heard from the loudspeakers set up by the village also set him thinking. One was "Education is the last thing to sacrifice," and another was "Building the road is the first step to becoming rich."

Before work started on building the road, he also mobilized people to spend half of the year on building the village's first primary school in 1995. Every stone, every tile and every ounce of labor was contributed by villagers themselves.

"I am just doing the right thing for the village. Thanks to the solidarity of our villagers, we have come this far," Mao added.

People in Xiazhuang now view the road zigzagging along the side of the mountain to the top as a hard-won access to cities that provides plenty of opportunities for study and work. What they couldn't predict back then was that 20 years after its completion, the road would make them a shining example of China's battle against poverty, attracting emerging industries and tempting young people to return to their hometowns.

CATALYZING RURAL DEVELOPMENT

The new road put the development of Xiazhuang on the fast track. It provided people with a safe and convenient way to sell agricultural goods and find jobs in the big cities. However, what really ushered in the roller-coaster of development was China's poverty alleviation policy.

Prior to the introduction of the policy in 2015, life in Xiazhuang changed a lot, but there were still obstacles to progress.

"Once the road was finished, Xiazhuang's poultry could be sold at a favorable price, as good as other villages. Before, it was difficult for us to ship our livestock out, so we could only sell smoked meat at a lower price," said Mao.

Around 2010, thanks to such economic improvements, villagers started building new brick houses, a sign of growing prosperity.

However, when it came to nurturing related agricultural industries in the village, things were not so easy, with Mao making several failed attempts. After a decade of exploration, the village finally struck lucky, adopting orange growing as the pillar industry. The oranges grew well in the local conditions, and taking them to market was no problem with the new road. Soon after, the poverty alleviation policy arrived, further catalyzing the process.

"It's really good that the government can see the grassroots needs and make such big efforts to improve the village living conditions," said Mao.

Thanks to the policy, many village families with young people at college or relatives in bad health, or other difficult situations, can receive support to make their lives better.

Also, with the support of this policy, many pioneers have grasped the opportunity to engage deeply in industry development in accordance with the local characteristics.

In 2020, Mao and nine other people were selected as the outstanding representatives of poverty alleviation at the national level. Most of them have been rooted in the village and revitalized it through a series of industries, such as the fungus industry, embroidery industry and others.

Although Xiazhuang was lifted out of poverty in 2015, the government has continued efforts to boost living standards, such as further improving the infrastructure, building more convenient vehicle-friendly roads, and introducing companies to develop the orange and tourism industries.

"I never imagined that one day, I would get to enjoy my life like this," said Yang Yuanding, sitting in the yard of his three-story farmhouse.

Like most villagers, Yang left the village after the road was finished to become a blue-collar worker in Sichuan, Guangdong and other provinces. Thanks to the poverty alleviation policy, the government provided him with housing subsidies, and he built a two-story house in the village.

The government helped develop the local tourism industry, making use of the village's road-building narrative, and many visitors were attracted by this "miracle" of perseverance. Soon the village became a tourism hot-spot. Yang was the first villager to transform his house into an agritainment resort, and in 2020, he made 100,000 yuan (about 14,300 U.S. dollars) in revenue.

With the business flourishing, Yang also built a new inn to accommodate more tourists. Also, in 2023, his two daughters came back to the village and opened another agritainment resort.

Sitting in his yard, Mao points at a building that is under construction, just in front of his house. "The owner of that house is not in the village, but he can earn money by renting the property to a company and letting the company turn their old house into tourist accommodation," said Mao. "Now, for Xiazhuang people, no matter where you are, you can make the money. Things have changed a lot."

In 2022, Xiazhuang garnered more than 700,000 yuan in tourism revenue, receiving 120,000 tourists. Meanwhile, the output value of the orange business was 1.5 million yuan. Villagers can now expect a per capita disposable income of more than 17,000 yuan, which is more than 50 times that of 1997.

THE NEXT GENERATION

From building the road to the development of local business, Mao has always been the backbone of this village, mapping the future and implementing policies. Even now, he has the habit of wandering around the village in the mornings and thinking about new projects.

"I think we could have a larger cultural square for villagers to dance and exercise in. Also, there are over 80 villagers who are over 60 years old. I want to set up a canteen for them," said Mao, who is now the Party secretary of Xiazhuang Village.

However, Mao is not alone in leading the village to a better future. Due to the economic and environmental changes in recent years, many young people have returned and are committed to making further improvements.

Yuan Xiaoxin, 31, is one of around 30 college graduates in the village. In October 2023, she was picked as the director of the village committee.

"At first, I felt very hesitant about accepting this offer, because I thought I was young and unqualified. However, when I thought about the sacrifices the older generation had made for the road, I decided to say yes," said Yuan, whose mother also participated in the road-building project.

Yuan said it's time for the young people to make their contributions to the village, and for the older generation to enjoy life. In fact, before being elected to her official role, Yuan had already injected some vibrancy into the village.

In 2021, Yuan had just left the internet sector and was looking at other career options. Seeing her parents doing well in the agritainment business in Xiazhuang, and knowing that the village had undergone lots of changes, she came back home in search of opportunities.

As she was looking around the village museum, an old photo of dye works caught her attention. Fascinated by this traditional craft, she decided to learn the necessary skills and go into business. By the end of 2021, she had established a tie-dying workshop and had become the inheritor of this county-level intangible cultural heritage.

Yuan is not the only young person who chose to return. More than 30 young people have chosen to settle down in the village, working as sightseeing bus drivers, primary school teachers, museum guides and so on.

To equip the self-made pioneers with more professional skills, almost every provincial-level region in China have held themed training classes on a regular basis, providing lessons on logistics, branding, e-commerce marketing, business management and so on. Also, the local governments send professional experts to provide on-site guides, helping the pioneers promote relevant skills and knowledge.

For example, Chongqing has held over 200 training activities in 2023 alone and each class was made up of 50 people. Since 2021, Chongqing has recognized nearly 7,000 people as pioneers.

"When I returned, I never imagined this degree of success," said Yuan. "In the future, I'll learn from Mao and contribute to building my hometown. Although it has seen some remarkable changes, it still has lots of space to grow." ■

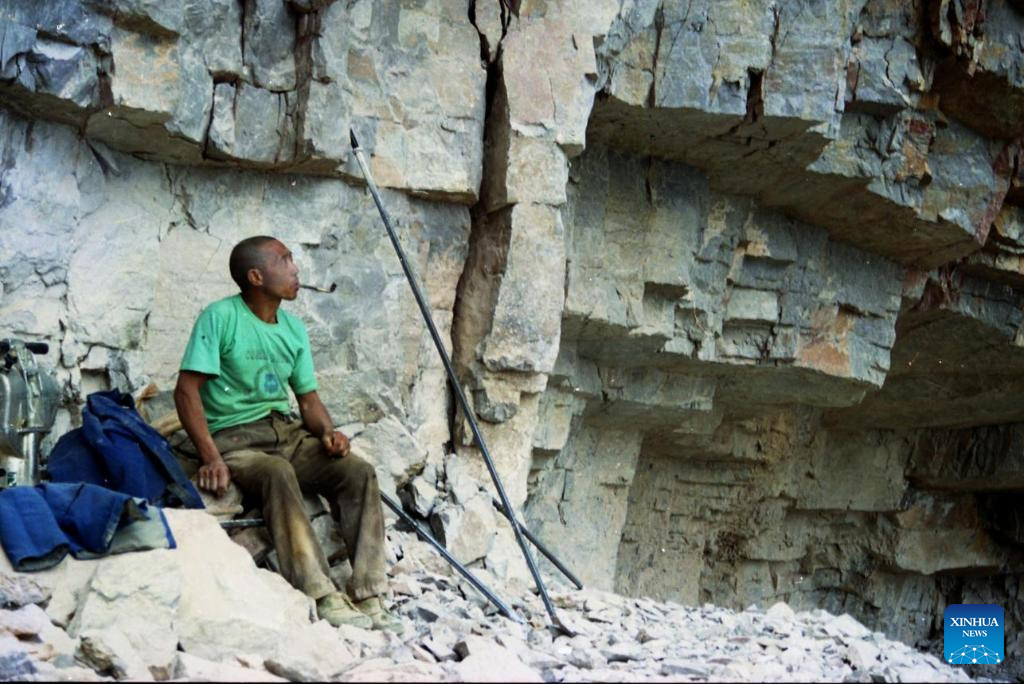

This file photo taken in 1998 shows a security guard fulfilling his duty on the cliff in Xiazhuang Village, Wushan County, southwest China's Chongqing Municipality. (Xinhua)

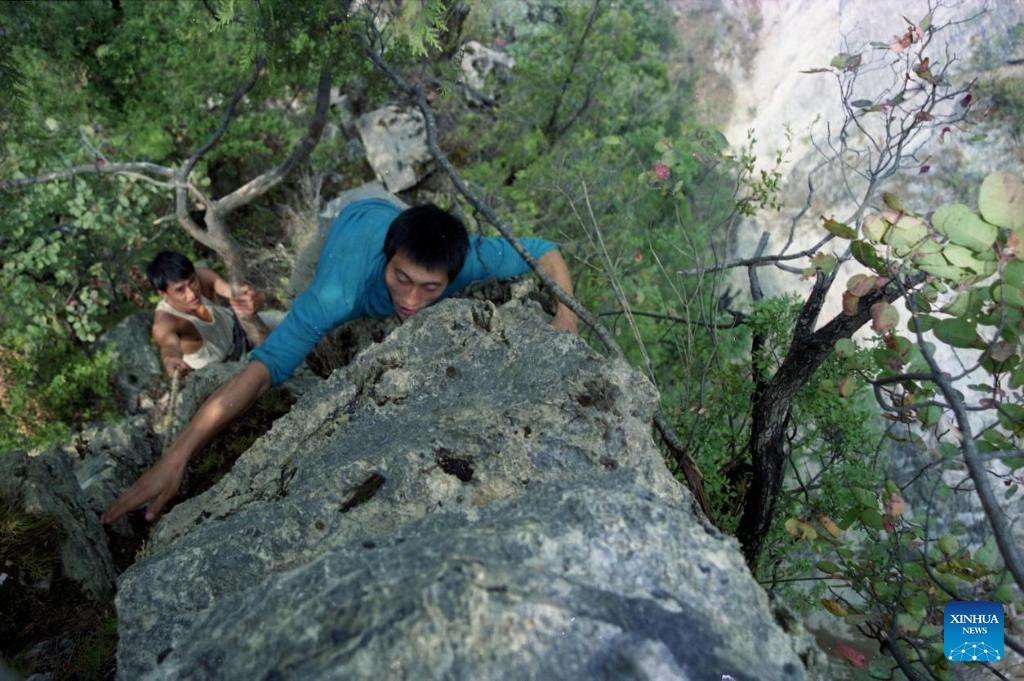

This file photo taken in 1998 shows villagers climbing up a cliff in Xiazhuang Village, Wushan County, southwest China's Chongqing Municipality. (Xinhua)

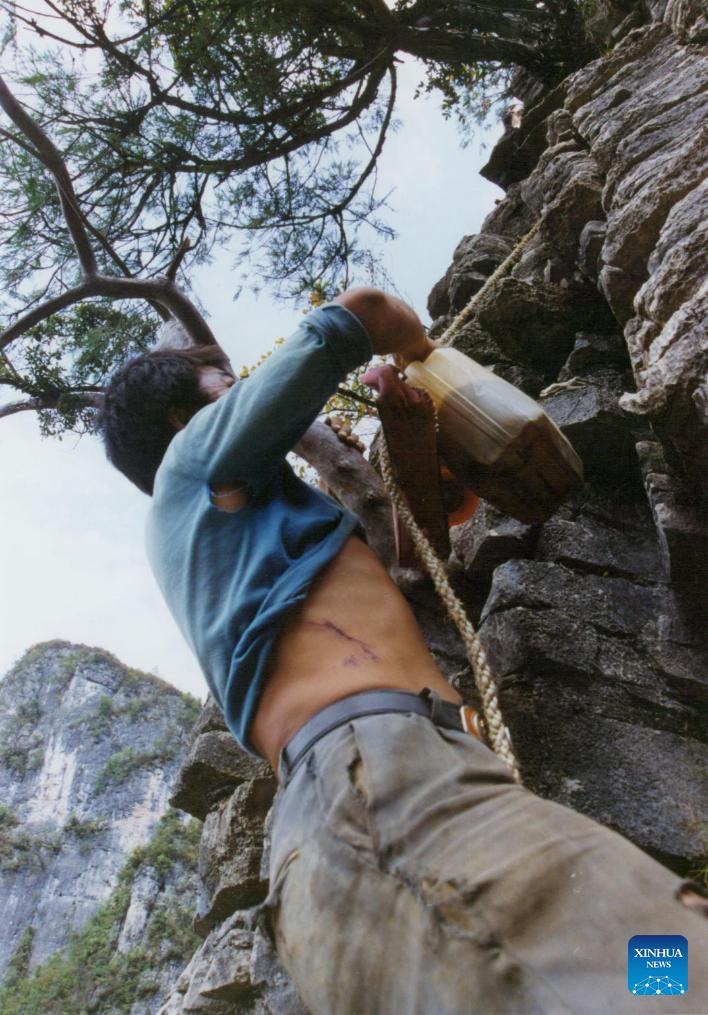

This file photo taken in 1998 shows a villager with scar left on his body while building a cliff-side road in Xiazhuang Village, Wushan County, southwest China's Chongqing Municipality. (Xinhua)

This file photo taken in 1998 shows villagers transporting supplies in Xiazhuang Village, Wushan County, southwest China's Chongqing Municipality. (Xinhua)

This file photo taken in 1998 shows villagers having noodles in Xiazhuang Village, Wushan County, southwest China's Chongqing Municipality. (Xinhua)

This file photo taken in 1998 shows villagers building a cliff-side road in Xiazhuang Village, Wushan County, southwest China's Chongqing Municipality. (Xinhua)

Yuan Xiaoxin does tie-dying work in Xiazhuang Village, Wushan County, southwest China's Chongqing Municipality on Oct. 10, 2023. (Xinhua/Huang Wei)

Yuan Xiaoxin (C) introduces her workshop for a team of reporters in Xiazhuang Village, Wushan County, southwest China's Chongqing Municipality on Oct. 10, 2023. (Xinhua/Huang Wei)

An aerial drone photo taken on Jan. 16, 2024 shows a cliff-side road built by villagers in Xiazhuang Village, Wushan County, southwest China's Chongqing Municipality. (Xinhua/Tang Yi)

This photo taken on Jan. 16, 2024 shows a view of Xiazhuang Village, Wushan County, southwest China's Chongqing Municipality. (Xinhua/Tang Yi)

An aerial drone photo taken on Jan. 16, 2024 shows a view of Xiazhuang Village, Wushan County, southwest China's Chongqing Municipality. (Xinhua/Tang Yi)

A villager works at a restaurant in Xiazhuang Village, Wushan County, southwest China's Chongqing Municipality on Jan. 17, 2024. (Xinhua/Tang Yi)

This photo taken on Jan. 24, 2024 shows a newly constructed road in Xiazhuang Village, Wushan County, southwest China's Chongqing Municipality. (Xinhua/Tang Yi)

Villagers pick oranges in Xiazhuang Village, Wushan County, southwest China's Chongqing Municipality on Jan. 24, 2024. (Xinhua/Tang Yi)