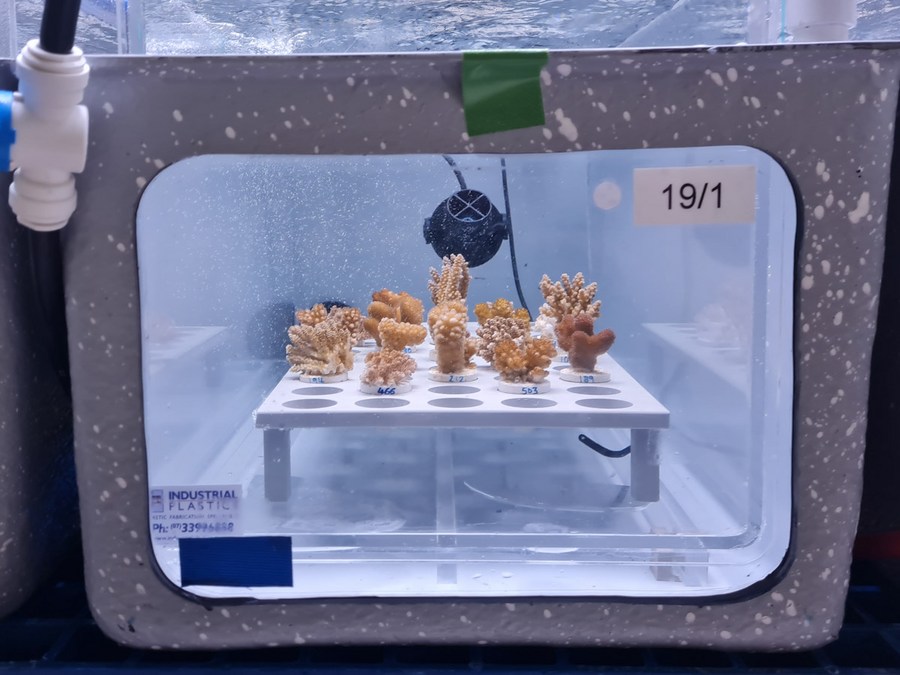

Photo shows some fast-growing coral species on the Great Barrier Reef slow down their growth rates when exposed to warm water. (Australian Institute of Marine Science/Handout via Xinhua)

Australian scientists found that fast-growing coral on the Great Barrier Reef is likely to be hit with a double blow of high mortality and slow growth during acute heat stress events.

CANBERRA, Jan. 12 (Xinhua) -- Warm waters inhibit the growth of fast-growing coral species on the Great Barrier Reef, a study has found.

In a research published on Wednesday, scientists from the Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS) found that fast-growing coral on the iconic reef is likely to be hit with a double blow of high mortality and slow growth during acute heat stress events.

The government agency's findings are a major blow to the long-term survival prospects of the reef as the world's oceans continue to warm.

Photo shows some fast-growing coral species on the Great Barrier Reef slow down their growth rates when exposed to warm water. (Australian Institute of Marine Science/Handout via Xinhua)

According to AIMS' Long Term Monitoring Program, recent increases in coral cover in the northern and central regions of the reef were largely driven by fast-growing species, which are common but more susceptible to marine heatwaves.

"Our results demonstrate that these fast-growing table corals, critical for reef recovery, have evolved strategies that are perfect to maximize growth in their current environment," Juan Ortiz, senior author of the study, said in a statement.

"But these initial findings may indicate that they have limited potential for adaptation to future hotter conditions."

Photo shows some fast-growing coral species on the Great Barrier Reef slow down their growth rates when exposed to warm water. (Australian Institute of Marine Science/Handout via Xinhua)

Ortiz and his team used the AIMS National Sea Simulator to track the growth of four coral species from one part of the reef at 10 temperatures ranging from 19 to 31 degrees Celsius over the course of a month.

The scientists were surprised by how consistently individual colonies of the same coral species responded to temperature.

Ortiz said the team will next expand the research to include more species from different parts of the reef.

"Low variability in their response to temperature could make it harder for corals to naturally evolve higher thermal tolerance. To gain more insights, we need to understand what is happening at a bigger scale and across more species," he said.■